In electronics, you may hear the term “quadrature” thrown around, perhaps in the context of quadrature encoders or quadrature signal processing. But what exactly does that mean? This article introduces the concept from a historical standpoint, going into detail on quadrature encoders.

The History of Quadrature

While you might assume that quadrature is a relatively recent term, it actually originated in Hellenistic times, when ancient mathematicians would attempt to model curving areas as squares. This may seem outdated in our age of integral calculus and pi calculated to trillions of digits, but consider how everything from house plans to circuit boards are still represented as having a square ft/m/mm value.

Rotary quadrature encoders perform a similar task, breaking up an unknown rotation into square wave pulses.

Quadrature Encoding: Rotary & Linear Quadrature Encoder

Quadrature, in the context of an encoder, means that two square wave signals indicating movement and direction are received in a pattern that is 90º, or 1/4 cycle, out of phase. Thus, it’s a pattern of square waves that are themselves squared (90º) to each other. These signals are normally produced via optical light transmission, or via physical contacts. In the case of rotary optical encoders, a disk with signal windows—through which light can pass—are arranged at an even spacing.

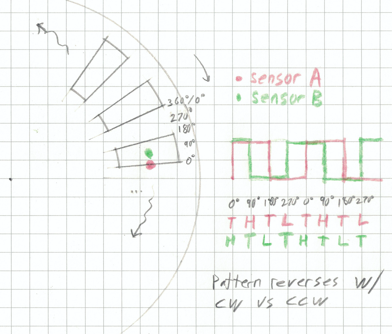

Quadrature phase diagram. Sensors here are high when exposed to window area, and low when obscured by ring

As illustrated above, when rolling clockwise, each disk window activates the offset sensors in a pattern of:

· Sensor A: 0º transition, 90º high, 180º transition, 270º low, 360º/0º reset

· Sensor B: 0º high, 90º transition, 180º low, 270º transition, 360º/0º cycle reset high

Individually, each pattern simply goes from high to low, either way the rotor is turned. Together, however, if traveling clockwise, when one sensor makes a particular transition, the other sensor will already be in a known state. For instance, when sensor A transitions from high to low at 180º, sensor B will read low when traveling clockwise. Alternatively, if sensor A transitions from high to low and sensor B reads as high already, it’s evident that the wheel is in fact spinning counterclockwise.

Rotational distance traveled can be measured by pulses on a single channel, and encoders are generally spec’d with a PPR, or pulses per rotation value. With the proper setup, however, the transitions of both channels from both high-to-low and low-to-high can be measured, allowing for quadruple the precision of a single-channel pulse measurement.

To perhaps state the obvious, this 360º pattern is not the total rotation of the wheel, but would normally be many individual on/off patterns that take place inside this overall rotational pattern. Additionally, the 90º offset is important here. If the sensors were 180º out of phase, both would transition at the same time, creating an indeterminate state during transitions that could throw off results.

Alternatively, some encoders use an offset pattern of windows for the two sensors, instead of the sensor offset arrangement shown here. Linear quadrature encoders can be constructed in a similar manner, but with the sensor windows in a straight line–as if “unrolled” –to determine distance traveled.

For more encoder info, check out the following articles:

· Understand the Different Types of Encoder

· Encoders vs. Potentiometers: Which Is Right for Your Project?